The directorial debut of one of Hollywood’s greatest screenwriters, starring arguably the greatest stand-up comedian of all time, that boldly and authentically tackles issues of poverty, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you had an active account on our previous website, then you have an account here. Simply reset your password to regain access to your account.

If you did not have an account on our previous website, but are a current print subscriber, click here to set up your website account.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

* Having trouble? Call our circulation department at 360-385-2900, or email our support.

Please log in to continue |

|

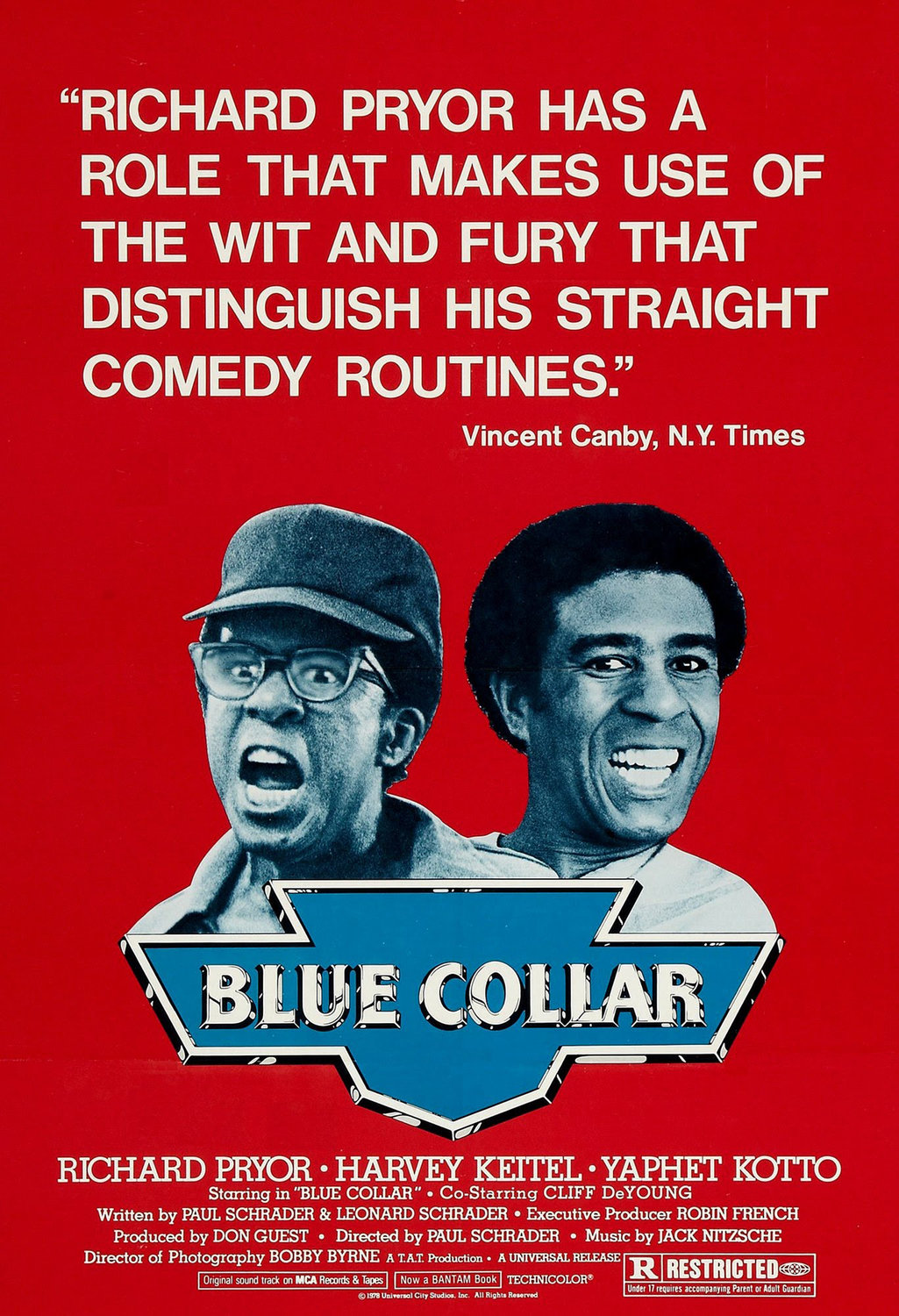

The directorial debut of one of Hollywood’s greatest screenwriters, starring arguably the greatest stand-up comedian of all time, that boldly and authentically tackles issues of poverty, racism, loyalty and labor politics in grimy ’70s Detroit — “Blue Collar” is a film whose time for wider reverence is nigh.

Paul Schrader had already penned the classics “Obsession” and “Taxi Driver” (and also 1974’s “The Yakuza,” a stylish Robert Mitchum vessel that eventually deserves its own place on this list) before he was finally allowed to actually helm a production. The resulting cinematic creation redefined not only himself but comedy icon Richard Pryor, finally giving him a chance to show he could be more than a fast-talking, wise-cracking clown.

The product of those twin artistic evolutions is a strange mix of hilarity and melancholy, an atmospheric and fatalistic masterpiece loved by both Siskel and Ebert, boasting a 100 percent “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and passionately championed by the disparate likes of Spike Lee and Bruce Springsteen.

Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto (all giving top-shelf performances) are a trio of Motor City assembly line buddies; luckless drones doing their very best to barely eke out an existence. They’re always tired and broke, beset by problems at home and work, being used by the bosses and their union reps alike — and they’re finally fed up with it.

Between after-work beers and a surreptitious night of rowdy carousing, the friends decide to make a grab for their own little piece of the American Dream. They rob the safe in the office of their union, and although they’re disappointed at first by the apparently light haul they quickly discover they’ve accidentally made off with something more valuable than money — but only if they play their cards right.

Of course, the bosses didn’t rise to the top of the economic food chain by playing by the rules or letting themselves be strong-armed by a couple of Joe Six-Packs. And everyone knows the game of life is more rigged than a Russian election. Quickly, the tension (and danger) escalates into the realm of deadly seriousness — and not all the boys will survive.

The leads are fantastic and the world depicted is palpably authentic. These guys were born poor and cannot gain any ground, no matter how hard they work or how cleverly they scheme.

Pryor is a wonder, alternating from hilarious to desperate, sometimes in a single scene (such as when his home is visited by an IRS agent who quickly realizes Pryor has fewer children than his tax returns indicate and Pryor, undaunted, smilingly stalls for time, becoming increasingly frantic, while his wife runs out the back and commandeers some neighbor kids to play the part).

Keitel is likewise wonderful, playing a man who is tough, proud — and obviously running on empty. In one heartbreaking scene, he learns his little girl has badly gashed her mouth trying to craft a homemade set of the braces she needs, but he can’t afford, out of wire. Yes, we understand why he goes through with the robbery.

But it’s only Kotto, playing a self-assured, streetwise ex-con, who understands the import of their unlawful decision and the events they set in motion.

Pryor puts his faith in the union and hopes to bargain for position, rise through the ranks. Keitel thinks the way to a better life is loyalty to one’s friends and doing for yourself: manifest destiny of the harshest sort. Kotto alone knows the higher truth, sees the bigger picture: The train of progress can just as easily be derailed from within.

In an era when so many are viewing the recent past with a decidedly too-rosy tint, talking easily of the supposed upward social mobility and dignity ensured by strong worker unions, and the paradise that was the American-made manufacturing industry of yesteryear, with quasi-religious fervor (and nostalgia’s stock is going up faster than an elevator on Adderall) today is the perfect occasion to revisit this criminally overlooked film. It is a pristine core sample of a certain way of life in a certain time and place, one somehow both better and worse than where we find ourselves at present, but similarly, hopelessly, American in every way.