Ray Steinberg remembers his Uncle Al fondly. He remembers stacks of brail books and baseball on the radio.

It’s a sweet, simple notion to share his charisma and adventurous vein, in …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you had an active account on our previous website, then you have an account here. Simply reset your password to regain access to your account.

If you did not have an account on our previous website, but are a current print subscriber, click here to set up your website account.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

* Having trouble? Call our circulation department at 360-385-2900, or email our support.

Please log in to continue |

|

Ray Steinberg remembers his Uncle Al fondly. He remembers stacks of brail books and baseball on the radio.

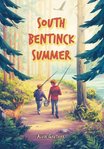

It’s a sweet, simple notion to share his charisma and adventurous vein, in publishing “South Bentinck Summer,” Al’s chronicling of two brothers in the wilds of British Columbia, for children and young adults. Or really anyone with the lightness and wonder of Al.

Alvin Gauthier passed in 1968 at the age of 78 in Southern California after having lived most of his life in Jefferson County. He moved to a farm off Discovery Road with his family in 1898 and in his early 20s, left to become a fur trapper in the Arctic, likely encouraged by the worlds he found within Jack London and Jules Verne novels.

Gauthier returned from the Arctic with failing eyesight and became fully blind before he turned 30. Blindness never curbed his voracious reading habit and proclivity for writing manuscripts, however.

“As long as I can remember, he was writing and reading; he read brail books constantly,” Steinberg said, “I remember these big boxes coming with Uncle Al’s books and he read them in brail but he was very well read.”

Steinberg grew up learning from Al, asking questions, discussing Jack London. During World War II, Al explained everything to him so that it made sense.

“I would go to him with things I heard or read in the world… he would answer, when I was very young,” he said.

It’s not just the love of stories that color Steinberg’s memories of his uncle. He also remembers Al taking him and his brother fishing for salmon over the years off Becker Point. His love of the outdoors lived on and flourished in blindness as well; he remained active in nature and in town, fishing, logging, building the family farmhouse, working in the defense industry in Kent during World War II. Uncle Al was a force. He understood the wilderness, geography, creatures of the woods, and wrote about it all, leaving a file of manuscripts to Steinberg that detail fur-trapping, canoe trips over the Great Slave Lake, Inuit friendships—a life rivaling the likes of London.

“Things people would like to know about,” Steinberg said. Now, they will.

Before his death, Gauthier moved to California, where he’s buried in Los Angeles (the elder Gauthier’s rest here in town at Red Men Cemetery and have legacies of their own in Port Townsend).

It would be years before Steinberg approached his literary inheritance.

In the 1990s, he was working as a librarian, continuing the family’s love of books, when he finally revisited his uncle’s writing.

He shared the “Bentinck” story with a writers’ group and, having received a positive response, decided to publish the children’s book.

Steinberg’s granddaughter, also a writer, did the first edits and the book was sent to Canadian publisher, Frieson Press, last year.

Now in his 90s, Steinberg still speaks sincerely and lovingly about the strength he saw in his uncle, the perseverance, and playfulness.

“He doesn’t look like a children’s book writer,” he mused.

But the vitality and earnestness of Al is clear in Steinberg’s voice as he rolls through the years, recounting.