Inge Norgaard Jensen, internationally renowned tapestry weaver and artist, passed away on Thursday, August 23, 2018. She was 66, and after a 10-month battle with uterine cancer, died peacefully in …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you had an active account on our previous website, then you have an account here. Simply reset your password to regain access to your account.

If you did not have an account on our previous website, but are a current print subscriber, click here to set up your website account.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

* Having trouble? Call our circulation department at 360-385-2900, or email our support.

Please log in to continue |

|

Inge Norgaard Jensen, internationally renowned tapestry weaver and artist, passed away on Thursday, August 23, 2018. She was 66, and after a 10-month battle with uterine cancer, died peacefully in her home with her husband and son by her side. A wellspring of creativity and a force to be reckoned with, Inge lived like she meant it and left an indelible mark with her being and her artwork.

Born and raised in Denmark, Inge attended the Aarhus Art Academy and completed a four-year apprenticeship in graphic design and printing. She then went on to specialize in tapestry weaving, spending the next three years studying and apprenticing with two of the top tapestry weavers in Denmark.

Inge's early works offer glimpses of her adventures sailing across the Atlantic Ocean and living in the Southern Caribbean. In 1974, while completing her training in Svendborg, Denmark, Inge met her future husband, Charles Haniford, who was restoring a single-masted, double-ended North Sea fishing ship called Karin. Four years later, equipped with a sexton and a spinning wheel, they embarked on a voyage that would take them through the Kiel Canal, south to France, Spain, Portugal, and the Canary Islands, and then west to Barbados and the Grenadines. After 18 months exploring the islands, Karin hit a reef, bringing to a close the seafaring chapter of their lives.

With their love of sail boats and woodworking still intact, Inge and Charlie came to Port Townsend for the Wooden Boat Festival in 1981, 37 years ago last week. Struck by the town's charm and character and excited by the abundant natural beauty and the lifestyle they could lead there, they quickly settled in.

Over the course of the next decade, Inge wove some of the Norse Mythology tapestries that established her reputation as a world class weaver. These include The Tree of Life (1984), Gefion and Her Four Bull Oxen (1987), Baldar's Dream (1989), and Heimdal's Nine Mothers (1986, pictured), which was commissioned by Silkoborg Hojskole in Denmark. Each tapestry depicts life-size figures and measures four to seven feet high and five to twelve feet across. The images are colorful, powerful and well balanced from afar. But to more fully appreciate their grandeur, it is helpful to look closely and understand some of the unique aspects of Inge's artistic process.

Inge described her technique as "free style Gobelin", a reference to the Gobelins Tapestry Factory in Paris, which was established by Louis XIV in 1662 and produced some of the finest European tapestries through the eighteenth century. Inge's tapestries were woven on cotton warp with threads spaced 1 to 2 centimeters apart. Depending on its dimensions, a tapestry may be woven from bottom to top with the finished lines running horizontally, or, if its width is greater than that of the loom's warp, then at a 90-degree angle, with the left side positioned at the bottom and the finished lines running vertically. With roughly 9 lines of yarn per vertical inch, her aforementioned tapestries contain somewhere between 700 and 1,400 lines of yarn in total, each pulled over and under the threads of the warp and patted down by hand over the course of six to twelve months. Many of her later pieces were twice as dense.

The yarn, too, is a work of art. Inge started with raw wool, washed it, and then spun it into spools of yarn, gently parsing and twisting the wool fibers over a castle wheel she turned with a foot pedal. To create the colors she wanted, she gathered indigo, blueberries, birch bark and other ingredients from nature, mixed the dyes with mordants so they would bind to the wool fibers when soaked, and then hung the yarn on a clothesline to dry.

In addition to mythology, Inge was always fascinated by the human experience and keenly attuned to it at both the societal and individual level. With wars raging in Somalia and Bosnia in the early 1990s, she cut gasoline cans into strips and wove them into borders to frame 22 tapestries, each depicting the face of a victim. In response to the Darfur Genocide in Western Sudan in 2003, she wove a series of red crosses, which she picked up again two years later in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. With "loose ends, cut edges and symbols popping out, falling in the wet heat", the series was meant to convey "the incredible need for help, repair and mending." (Tapestry #18 from Red Crosses series, 2002 – 2006, pictured in portrait.)

Years later, on the floor of the ladies' room in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, she found a crumpled note written by an expecting mother. The first line read, "Unborn child I don't really know what should I do now." Inge felt the girl or woman's words needed to be heard, "exactly as she had written them", so when Inge found a white linen nightgown several months later, she knew what to do. She enlarged the original script and embroidered it in red around and around the dress, which she hung from the ceiling on an old wood hanger so it could move gently in the air.

Other pieces were lighter and illustrated her versatility, playfulness and desire to push the boundaries of convention. She carved ladies with wings in slabs of marble and made collographs of her mother's dog, Tenna, snoozing in a plastic cone collar. Out of recycled plastic milk jugs, she cut dozens of petals, and with copper wire and ink, arranged them on eight mat boards that, like pages of a flip book, show a box of flowers being tipped over.

One of her more recent favorites was inspired by three photographs she took in Vietnam of large fishing nets suspended above the water by poles and rope. She blew up the images to several feet in size, divided them into grids consisting of equally sized rectangles, taped the pieces together and then wove small tapestries of just a few of the sections. Delicate lines from the photograph are carried through the paper and textile sections of the grid, connecting the piece visually and reinforcing the strips of archival tape that, in a break with tradition, appear on the front of the work. That each individual tapestry is an abstraction of the whole and shares the same color tones makes them both more cohesive and capable of standing on their own. (First Net from Reaching Beyond series, 2013 – 2014, pictured in portrait.)

"What makes Net art" wrote Lois Harbaugh, former President of Northwest Designer Craftsmen, in the Fall 2014 Whatcom Museum newsletter, "is the pleasure it provokes aesthetically and intellectually. Inge's choice of imagery (rich in visual and metaphorical layers), her aesthetic sensibility (involving sensitive line and sublime color), her grand risk-taking in how she portrayed her subject – all give the viewer an opportunity to explore. It provides an absorbing experience of looking, requiring both eye and mind."

Although she worked across many mediums, Inge always came back to tapestry, and often back to nature. Next to mythology and social and political topics, it is the most prevalent theme in her body of work. The sea, which she could watch for hours when studying its "always changing and moving surface," featured in a number of pieces, but none more prominently than Song of the Ocean (1999), which masterfully captures the movement and tranquility of waves.

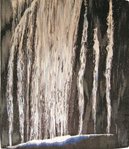

Marymere Falls in Olympic National Park presented her with an opportunity to explore water moving in a different way. In 2013 interview with Viviann Kuehl for Living on the Peninsula published by The Leader, Inge recalled her visit to the waterfall: "I was fascinated by the water tumbling and moving. It's the opposite of tapestry, so still and locked. I thought it's an impossibility to put that in a tapestry." So that's what she set out to do in Energy (2002, pictured), which was displayed at the Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle, Washington in 2008, and alongside William Kentridge and 22 other artists from 16 countries in the "New Art of the Loom: Contemporary International Tapestry" exhibition, which traveled to seven locations in the United States and Canada between 2013 and 2015.

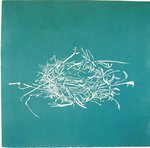

As a weaver, wife, mother and matriarch, Inge was also drawn to the image of a bird's nest. A nest is, of course, itself a weaving. Functionally, it provides the warmth and security chicks need to survive and mature, and symbolically, it represents home. Aesthetically, the intricacy can be astounding.

In a series of tapestries and woodcuts produced between 2007 and 2013, Inge sought to "step away from the traditional image of a nest and cut it to the bare minimum." As she described it, the fascination was in "studying random lines in order. Instead of pure abstraction, build it from a bird's woven creation." Her Nesting 2 tapestry (2009) was included in Textiles: The Art of Mankind, a definitive text on global textiles by Mary Schoeser (Thames & Hudson, London, England, 2012), and a quartet of her woodcut prints are pictured here.

Inge's work has been displayed in over 100 exhibitions throughout the world, including over a dozen solo shows. She was awarded residencies in Ireland, Spain, Denmark and Alaska, and was a long-time member of the American Tapestry Alliance, Northwest Designer Craftsmen, Tapestry Artists of the Puget Sound, Corvidae Press in Port Townsend, and The Funen Graphic Workshop in Denmark.

A Dane at heart and United States citizen by choice, Inge cared deeply about America, its role in the world and its resolve to do right. She read widely, loved to travel and constantly sought out new perspectives. An exquisite cook with a quick wit and refreshing candor, she relished hosting family and friends for lively discussions around the dining table. Selfless and kind, she endeavored to connect with everyone on a personal level and encourage others to be bold and true to themselves.

In her 2013 interview for Living on the Peninsula, Inge recalled a recent exhibition she attended in Copenhagen, 36 years after she first showed there. "It's much different now, but still relevant and very exciting. It's a very good reminder that we have to keep evolving. We can do things we never could back then. It takes a lot of courage to break these boundaries. It takes years to change, and then you have to believe in yourself, and when you do it's wonderful."

Inge was preceded in death by her parents, Knud and Ellen Jensen, and is survived by her husband, Charles Haniford, their son, Lief Haniford, and her sister, Judith Pederson. A ceremonial portion of Inge's ashes were buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery on Friday, August 31, 2018, and the remainder were scattered with rose petals where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets the Puget Sound.

In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to American Tapestry Alliance, Corvidae Press, The Nature Conservancy, or Doctors Without Borders.

Inge's artwork can be viewed at: https://ingenorgaard.com.